The dark truth of cinema, the truest American art form outside of television, is that it was founded as entertainment for the white norm. Whiteness is seen as a given and a status quo of early cinema, while any other race, especially black, is seen as useful only as entertainment. There was a need (and there remains a need) for an antecedent to a starkly monocultural screen, which was for a time filled by a brave few independent filmmakers. Their films, a hodgepodge of melodramas, genre pictures, and the unclassifiable, were at the time characterized as a single genre- “race films”.

~ Race Films Spotlight: Prehistory, Oscar Micheaux, and Body and Soul (1925) ~ Race Films Spotlight: 1920s Oddballs ~ Race Films Spotlight: Hallelujah (1929) ~ Race Films Spotlight: Paul Robeson and Emperor Jones (1933) ~ Race Films Spotlight: 1943’s Black Musicals

Around the same time as Micheaux Film and Book Company, another producer, the white Richard Norman, entered the race film game, seeing an untapped audience niche and hoping to reconcile race relations of the time. At the opposite end of the race film spectrum to Micheaux’s “educational films” was Norman’s The Flying Ace (1926), an attempt at pure entertainment riding on the coattails of the latest Hollywood craze- airplane flicks. Lightly notorious for not taking place during World War I, nor featuring an actual flight sequence, Ace is really a stodgy, wafer-thin detective mystery, but once freed to stage fight scenes and attempt flying practical effects, executed with earnestness to the point of endearment. The most obviously entertaining portions of the

film star Steve “Peg” Reynolds as his namesake, the Flying Ace / Railroad Detective’s one-legged sidekick, who manages to steal the film entirely out of the utility for his crutch as a prop- Peg plays his crutch like a banjo, inserts a long-barreled gun into a secret compartment in his crutch whilst saying “I’ve had enough of this hocus pocus”, uses his crutch to peddle a bicycle whilst using the gun-crutch to shoot at bad guys, and finally apprehends the crooks by using his crutch like a scarecrow. Beyond amusement, these scenes are a reminder that independent cinema created venues of expression for other minorities besides African-Americans.

A third production company, The Colored Players Production Company, entered the fray in 1926, founded on the principle of racial cooperation by white producer Will Starkman and black vaudevillian Sherman Dudley. “Players” were all black; the crews were white, while the production teams were integrated. Films made by the company stayed close to Micheaux’s precedent, making melodramas about issues of race, but employed higher production values and classically trained actors to distinguish itself from the competition (a decision that ultimately harmed the company). Its last and most notable film, Scar of Shame (1920), is a far more attractive film than any of Micheaux’s, but also a more impersonal one, with intertitles that read as if written by a bleeding-heart tin man. (A choice example, spoken by a character after stopping a near-beating: “This is another instance of the injustices some of the women of our race are constantly subjected to, mainly through lack of knowledge of the higher aims in life.”) An attempt at tackling social stratification and misogyny among African-Americans with its own strains of classism and misogyny, Shame is also among the least involving race films of its era.

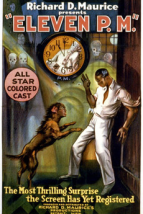

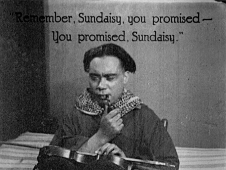

A silent race film that could makes no claims for blandness was Eleven P.M. (c.1928), by Richard Maurice. Little is known about Maurice; he founded a production company, the  Maurice Film Company, in 1920, proceeded to make a lost film called God’s Children, then disappeared from the public eye until the release of P.M. The film, on the short list of the most bizarre silents ever made, takes place within the dream of a writer, who is attempting to write a story about man’s ability to transmogrify into an animal; thereafter, the plot can hardly be explained, beyond an addendum regarding the constantly variable ages and net worth of the characters, and a further addendum regarding the sheer strangeness of its ending. The film is deeply incomprehensible and thus deeply unpleasant, but has attracted a cult following for the

Maurice Film Company, in 1920, proceeded to make a lost film called God’s Children, then disappeared from the public eye until the release of P.M. The film, on the short list of the most bizarre silents ever made, takes place within the dream of a writer, who is attempting to write a story about man’s ability to transmogrify into an animal; thereafter, the plot can hardly be explained, beyond an addendum regarding the constantly variable ages and net worth of the characters, and a further addendum regarding the sheer strangeness of its ending. The film is deeply incomprehensible and thus deeply unpleasant, but has attracted a cult following for the

same, and for its limited but enthusiastic use of unusual angles, cuts and special effects. Whatever it is, P.M. is a presence.

Check back next time for analysis of Hallelujah (1929), the first studio-produced race film.